British born, Los Angeles based photographer Phil Knott began shooting professionally in 1997, jumpstarting his career in London. Over the past three decades, he’s captured some of the most iconic names in music. From A$AP Rocky’s first album cover, to Justin Timberlake’s Vibe cover, Knott has taken part in his fair share of legendary moments, documenting the humanity of some of our culture’s greatest icons through his portrait work. His photographic journey has taken him to New York, and currently Los Angeles, allowing him to cross paths with genius-level talent.

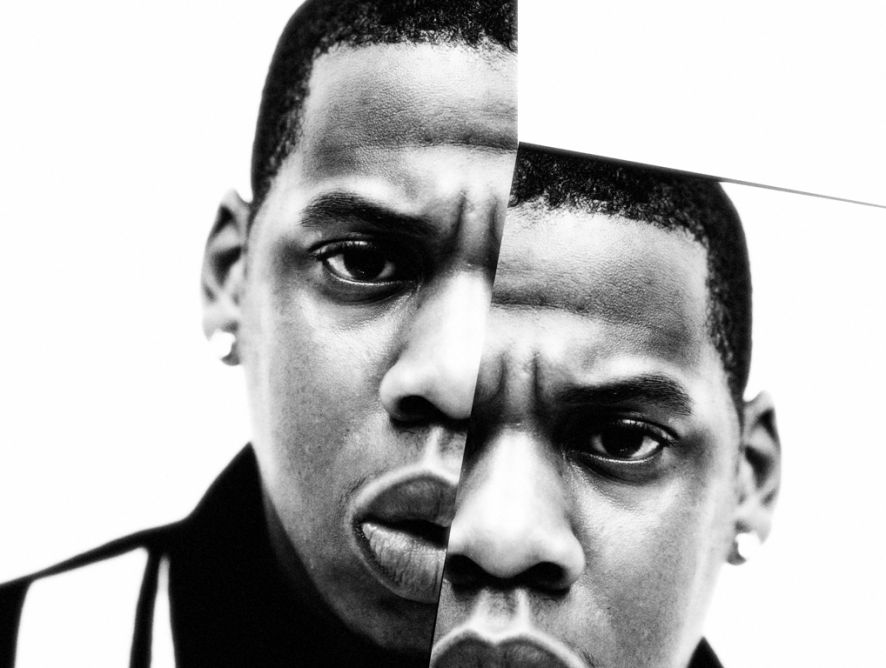

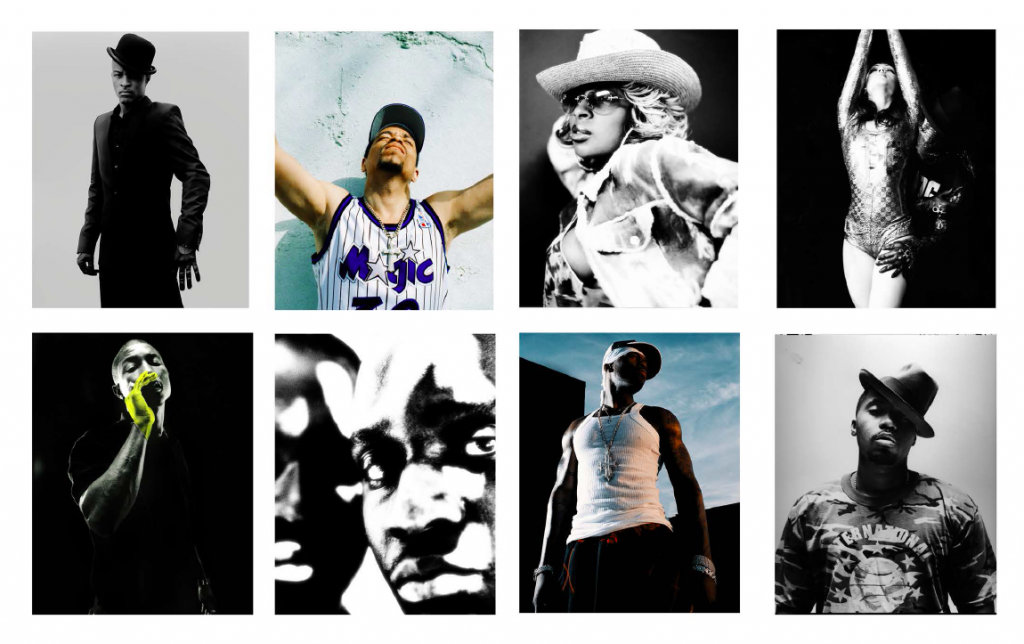

In September, Knott exhibited a collection of portraits at Mixduse Collective in Brooklyn at a show called Heroes & Legends that featured just that. The solo exhibition included mainstays of the golden era of New York hip-hop including: JAY-Z, Guru, RZA, Nas, and more. He’s following that up with his recent show called I Love You Amy that features 20 pre-celebrity photos of Amy Winehouse that opened this past Thursday.

After being connected through a mutual friend, I jumped at the opportunity to learn more about Knott’s journey and craft. Once the background stuff was out of the way, he went into detail about his approach to portraiture, how location plays into his output, Instagram’s effect on commercial photography, and more.

Whether you’re a casual photographer or pursuing a career, there’s something to be learned from Knott’s below account of his years spent behind the lens.

Let’s start with a bit of your background, and what life was like growing up in London.

PHIL KNIGHT: I started shooting photos in ’97. I worked at Ray James’s CLICK Studios in London. We shot everybody. At the time, I was doing a degree at Harrow Polytechnic. I realized that I learned more at the studio in a month than I did in three years at the university. I saw firsthand how the photography business worked. I worked for Jean-Baptiste Mondino. He was so cool. He would use like four rolls of film on a campaign. He would shoot these polaroids that looked absolutely amazing. That changed everything. I was like, “This is it. I want to be you!” That was the beginning of my photography. It was the early days in the London scene. Things were vibrant. There were these fantastic magazines like The Face—which I would work for a lot—that would allow you to do what you want. Mo’ Wax was big at the time, and I would work for them. Basically, I got paid in records from Mo’ Wax. So I’ve got a collection of everything that it has ever done. That’s the only collection of records that I’ve got. I threw everything else away.

Talk a little bit about the music scene in London back then, and how you got immersed in it.

Back then, the internet was just an infant. It wasn’t really affecting the labels. So all of these bands were getting signed. There was money from people buying records. The venues in London have always been healthy. I worked with a label called 1234 Records. There was a real scene where all of these up-and-coming people would hang out together. You could go and shoot a band, and get paid for it. You’d go see a band, meet them, and shoot them the next day. The money would come from the record label. You could shoot four or five bands in a week. I was in New York, and I remember when Tower Records closed. I was like, “Oh shit, this is it.” I think everything was in confusion. I don’t think the labels were prepared because they thought it could never happen.

Daft Punk by Phil Knott

How did you transition from London to New York?

It was easy. London was like New York; it was a natural progression. A lot of the bands that I had been shooting were coming from New York. I was dipping in and out doing jobs. Then, my office, Jan Stevens’s ESP, opened up there, which made it a lot easier. I had a base. After a while, I realized that I quite like this place. It was exciting. It wasn’t like London—but it kind of was. It was a melting pot of cultures. The language was the same. It wasn’t like going to China or something. It was an inspiration, all of the graffiti and all of the art. At that time, it was only in New York. If you travel to various cities, you see the same kind of artwork on the walls now. Back then, things were sort of New York-specific. Suddenly, it became universal. So when I got to New York, there were these beautiful pieces on walls. I had never seen anything like this. And that was my inspiration, along with the quickness of the city and the compactness of Manhattan. This was in 2002.

How did you get immersed in hip-hop culture, and start shooting with these up-and-coming rappers?

I had a contract with the late, great George Pitts at Vibe. Through George, I used to shoot a lot of stuff. Through Vibe, I was in the running to shoot all of these artists. It was probably through that, XXL, and Complex. That was my access to all of these lovely people. I shot Baby and Lil Wayne in Miami. I shot Kanye for FHM. I’ve bumped into Kanye quite a few times. He was always a sweetheart—and look at him now. He’s a superstar. And he’s still here. He’s still at he top of his game.

Kanye West by Phil Knott

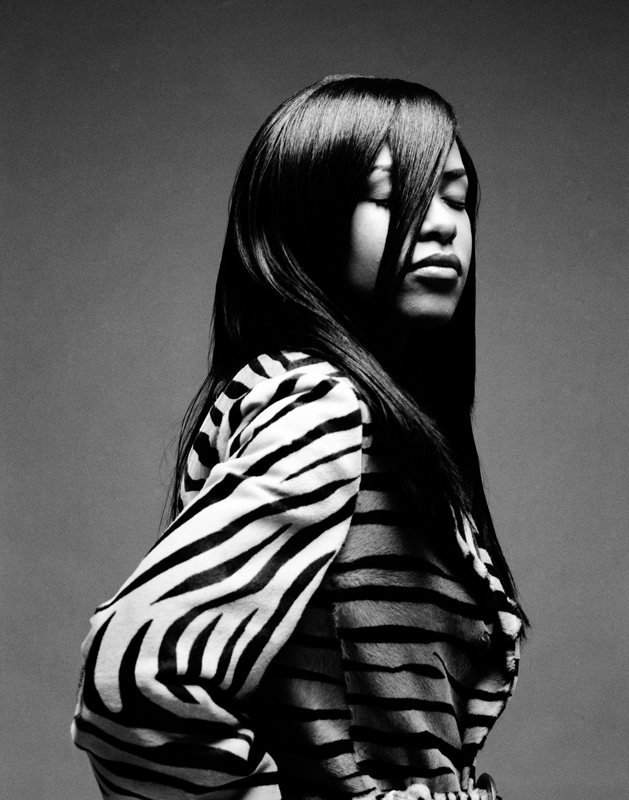

Speaking of superstars. What’s the backstory on how you met Amy Winehouse?

The Frank album was out, and she really sort of wasn’t anything then. She wasn’t in the newspapers. I didn’t know too much about her. She was just this beautiful-voiced girl. She was kind of shy. To me, it was just another artist or band that I was doing. But she was really special. It was one of those nice days, and we kind of dipped all over West London. There wasn’t an entourage behind us. It was just me and her with a few people around taking pictures. There wasn’t any sort of publicity there. So we just went around and took pictures. It was not a big deal. It was sort of magic. At the end of the day, it’s about the picture. Nowadays, it’s just kind of different. There are all of these people that you have to deal with.

Amy Winehouse by Phil Knott

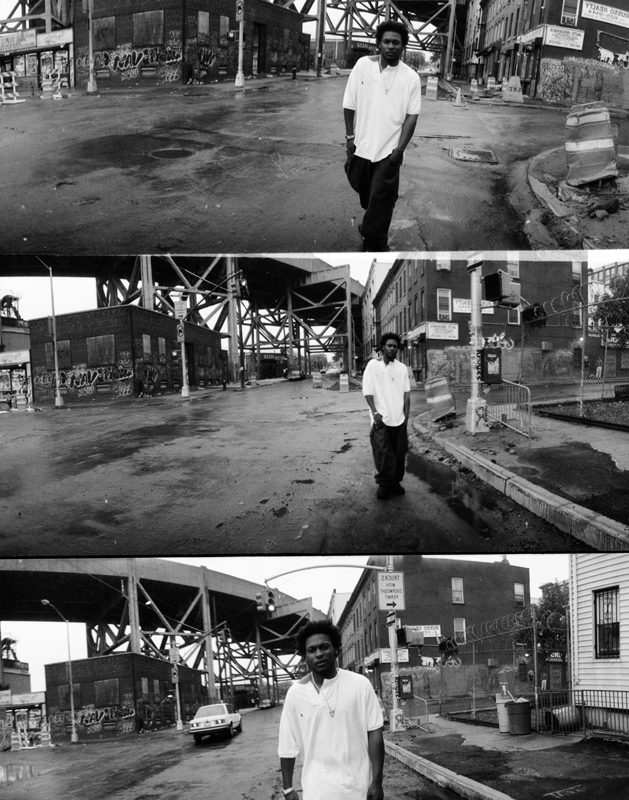

You shot A$AP Rocky right at his ascension.

I did his first album [Long. Live. A$AP]. With rappers, you’re used to people smoking weed and having a bunch of people around. But the A$AP crew were different. Everybody was young, and everybody was doing something. One guy was doing the video, one guy was making jewelry—you know what I mean? Everyone was productive in that group. And that sort of struck me straight away. There was nobody hanging around doing nothing. Rocky was really nice. We went to Harlem where he’s from to shoot. The art director had the idea of putting the black and white flag—it’s upside down. I came to find out that you only have the flag upside down when the country is in distress. They were really in tune with what was going on back then. So that was an iconic record sleeve. But it wouldn’t have been iconic if the music was rubbish.

Could you already see where Rocky’s career was going just from meeting him on the shoot?

I knew the kid wasn’t going to waste any time. That’s the impression that I got from him. He was confident, but not arrogant. I didn’t know how respected that first album would be. I didn’t know he had a big following. He was just sort of this cool kid. In hindsight, his longevity is quite amazing.

I was told that you don’t use social media.

I’ve kind of been forced to, but I like it. For me, I use it as a diary. At the moment, I’m doing a project called Shadow Land. I’ve done some incarnations of it in a book called Masters of Light. It’s one of those things that I’m carrying on now. I live in L.A.; I’m seeing a lot of color. New York was all black and white—but over here, I’m really seeing color. So I’m doing this abstract project based on shadows—the way they form, patterns and stuff. Basically, I’m looking at light. And I think that if these are blown up really big, they will be really beautiful. So I’m trying to find a picture everyday rather than posting the same one.

“There’s this whole list of things from back in the day that went into your craft. And now, with these fantastic iPhones, you don’t have to do that. But you do have to have a good eye. So however you get there, get there. It doesn’t matter.”

What were your thoughts on Instagram when it launched as just a photo sharing app?

I wasn’t really fond of it. I found the whole thing quite overwhelming. Once in a while, I would see beautiful stuff. There were beautiful pictures from all around the world. But a lot of times, I would see a lot of rubbish—loads of portraits. How many pictures can you take of your face and post it there? But then, I was talking to a friend, and we came to the conclusion that that’s what these kids do. I couldn’t think of anything worse than posting a hundred pictures of me on a fucking website. I just try to post inspirational things. And I don’t really tag it that much. The unfiltered thing… It’s like, “Look at me, I took a nice picture and it’s unfiltered.” Okay, just put the fucking picture up, tell everybody where it is, and leave it at that. But it doesn’t work like that. My friend said that you have to become a personality. I think I’m irrelevant—but my pictures are really nice. It’s the way of the world. This is the way it’s going. I don’t know if it makes it right. But when I look at Instagram, I’m overwhelmed by all of the nonsense out there.

Back in the day, when the Box Browning was invented, it meant that every household could have a camera. It was affordable. Their thing was just point-and-shoot, and you’d get the perfect picture. So families started to have cameras in their homes; they’d take a lot of pictures, and record their daily lives—things that we might find banal. They’d shoot a lot of things to prove they’d been there, especially the Japanese. They were like, “Let’s travel.” They were armed with two cameras, and they would take a picture of everything. It was to show that they had leisure time, and were not always working.

Have you noticed any impact on the commercial photography landscape now that social media is so prevalent?

I don’t have a problem with it. I came up working for a studio. Then, I went out on my own. Things have changed. If people are getting discovered through social media, good for them. If you’re really passionate about what you’re shooting and people like seeing it, then you don’t have to go to university. You don’t have to do what I did. But for me, I learned about film, dark rooms, and developing. There’s this whole list of things from back in the day that went into your craft. And now, with these fantastic iPhones, you don’t have to do that. But you do have to have a good eye. So however you get there, get there. It doesn’t matter.

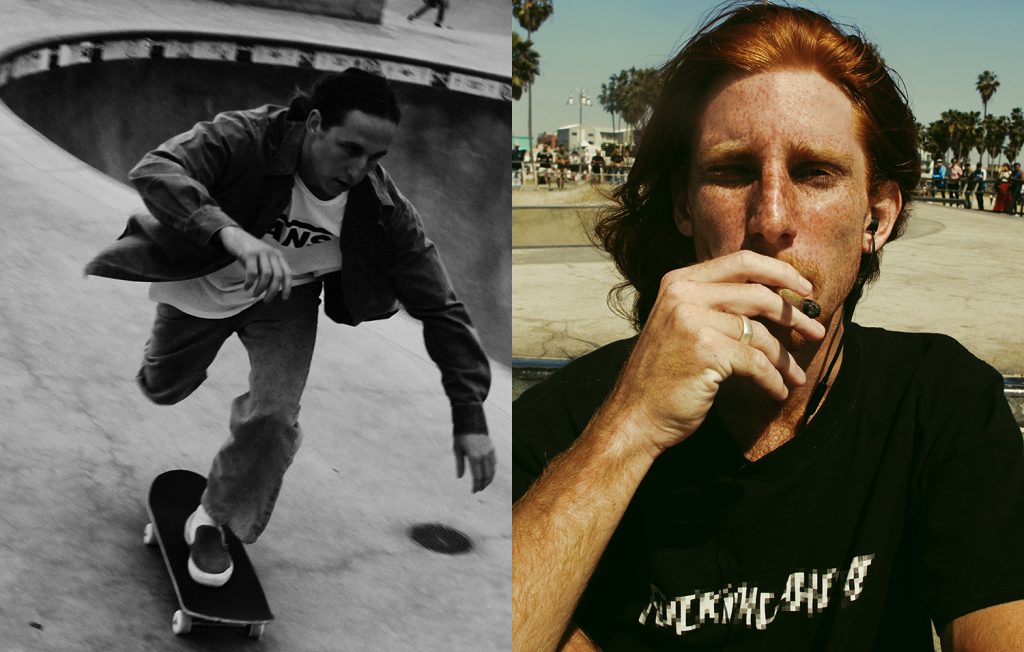

From Phil Knott’s series focusing on skaters in Venice Beach

What prompted your move from New York to L.A.? And besides the obvious, what’s your impression of the differences between the two?

I like the idea of going forward. If you think about it, you’ve got London, then New York. You’re not going backwards to Europe. In terms of going forward, the only place that I can go is L.A. From there, I don’t know. Maybe you could work your way around the world or something. I moved here for the light. I had done eight or nine years in New York, and I wanted take a different picture. The light is different here. And I was sick of the weather [in New York]. I was sick of the humid summers and freezing winters with a little month in-between when it’s nice.

When I moved to L.A., I was lost! People told me it was going to throw me out here, and it did. It’s spread out. It’s only now that I’ve kind of put things into perspective in L.A. It’s different. And things are slower here. If people say they are going to do something, it might mean in a couple of weeks or a month. In New York or London, if we say we are going to do something, we do it tomorrow.

The thing that I don’t like is the image thing. In New York, people are more direct. People think they’re being quite rude, but they’re not. They’re just being direct. Go to Brooklyn; they’ll tell you what time it is. [In L.A.], everybody is trying to project an image. It’s about a BMW or something like that. It’s about the appearance—and I do have a problem with that. Just be straight up.

From the Heroes & Legends show at MIXDUSE

Talk about your Heroes & Legends show and your other upcoming show.

It’s a collection of my best [photographs of] heroes and legends. There’s Questlove, Cam’ron, Boy George, Guru—which was kind of weird because I shot him in London. He was this weird rapper dude that was hanging around the neighborhood where I lived—which was kind of nice. I’ve got Aaliyah. I’ve got the early days of Daft Punk when they were just getting discovered before their music became really elaborate. So there’s all of these wonderful faces that came in front of my lens, which I’m very grateful for.

I’ve worked for some magazines. There’s a magazine called True—I don’t know if you remember that—that was the big access to people like D’Angelo, all these sort of people. Through Vibe magazine I shot Justin Timberlake for the cover. In all fairness, I didn’t really know about him. I didn’t know why he was such a big deal. It’s all in hindsight. But those are the people that sort of persevered. It’s like a marathon. It’s a longevity thing. Some of them might go away for a minute, and then they come back. If you’ve got a good solid foundation, there’s no reason why you can’t come back. You can go quiet. But if you’re good, you do come back. Look at Mick Rock, those collection of images with Bowie and everybody. I think that they’re one roll of film taken in London. Because of the nature of the artist that he shot, some of them have become icons, his photography goes with it. He was the one recording them. He was the person who was there.

The second show is I Love You Amy. It’s about 20 pictures that of I shot with Amy Winehouse. One [roll] was an outside location, and the second was at a studio. I’m glad that I left them for a while. They’re so beautiful. They’re attractive pictures, really nice. [She has] no tattoos, and it’s in this beautiful light. You can see her passion and what not. That’s what I was looking at. In hindsight, looking at them now, I’m like, “Wow! They’re beautiful. They’re really pretty.”

D’Angelo by Phil Knott

What do you think makes a good portrait, and how do you go about creating one?

There’s loads of factors. At the beginning, you’re working out the lighting. I like to keep it really simple. I don’t like busy backgrounds. The eye moves around. And I want you to concentrate on the subject. And I want the subject to be passionate, or introverted, or extroverted. I want something to come from them. So I’m looking to see how their face moves—a little shyness in the eyes, a cheeky little grin or something. It’s the way you move off camera. I don’t like those pictures where people look like they’re having their picture taken at a wedding—wide-eyed, like, “Look at me.” I like people to almost not really look at the camera. We should look at them. I find that more precious rather than someone looking straight at you. It’s almost like you’re hidden, and they’re not seeing you. I find that more interesting.

Aaliyah by Phil Knott

Aside from the I Love You Amy show, what projects are you currently working on, and what else is coming up on the horizon?

I’ve been trying to do some painting, and getting back to doing some artwork. I used to do a lot of coloring. I shot a load of people for a place called Homeboy Industries in L.A. It’s basically a rehabilitation for prisoners, gangsters, and what not just to get them back on track. I shot it as a tattoo thing for my friend’s production company. Somebody was doing a video, and he asked if I’d like to do some casting for it. So I spent a couple of sessions shooting these, not scary [guys], but [they were] the real deal. [They were] covered in tattoos. But not hipster tattoos, everything on that face was for a reason. The post code, what street I’m at, which meant what gang you were [affiliated] with. I was fucking fascinated. I’m working to make them very big using a few techniques, and I’m incorporating [images of] flowers. So I’m getting back into artwork. But I’m taking my time with it, because I want it to be good. I see a lot of flowers in L.A., and I like the idea… These people are beautiful flowers, and then it dies. So I’m mixing in real stuff and individual art pieces that I’m passionate about. I want to make it mean something.