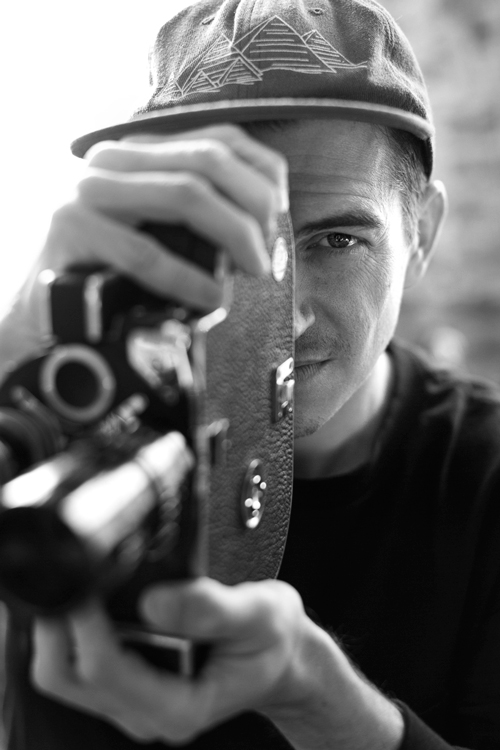

One of the biggest shifts that we’ve seen in skateboarding over the past couple of years is the rise of the small independent brand. Josh Stewart was on the forefront of that movement. Through his critically-acclaimed Static video series, Josh was able to create a cult-like following. He then decided that he wanted to share the work of other indie filmmakers with the world, so he started the Theories of Atlantis website and opened up an online store. Through the connections that he made producing videos, he organically began distributing small skater-owned brands started by the people he filmed video parts with.

Over the past several years, the brands under the Theories umbrella—which include Polar, Hopps, Isle, and Traffic—have become wildly popular with skateboarding’s core audience. At the same time, Josh launched the Theories clothing brand as an extension of the aesthetic that he created through his films and site. In an era where small independent companies are emerging as the dominant force in the skateboard industry, Theories is definitely something that you should be aware of if you’re not already.

What is it about New York that you find conducive to making skate videos as opposed to California or other places?

JOSH STEWART: There’s two things. The art direction of the Static videos is based on trying to capture the essence of being in a city and street skating. Beyond that, I wanted them to have this darker, creepier vibe. London really captures that feeling. You have this Industrial Revolution-era architecture mixed with older architecture. It’s such a contrast to what I was used to growing up in Tampa—everything there is new and made from stucco and cinder block, there’s really not much character. A city like New York is the perfect backdrop for filming skateboarding. The industry has been so heavily based in California, so the backdrop is schoolyards, strip malls, and kind of bleak and generic. So I wanted to do something different that was more than just a skate video—I wanted to do something that had texture to it. In New York, the city adds a cinematic feeling to everything.

You started Theories [of Atlantis] initially to distribute the Static films, then you started distributing other indie films, and now it’s evolved into a full-on skateboard and clothing distribution. Can you tell the story of that progression?

Through the period that that all occurred, the Internet [had] evolved a lot. The way that I used to do it is that I would build a website for each video. Those sites were the place where fans of the series could go to see photos and a blog about what’s going on, and then eventually I would put up a storefront that I would sell the video on. The first couple were just static2video.com and static3video.com. After Static III, I wanted to start carrying other filmmakers’ videos. It seems like now, there’s a lot more support for underground skate videos. At the time when we started, there were maybe a few a year. If I found out about a rad video from Japan or Australia, I wanted to carry it. So, we were selling our video, but we also started curating other projects that I respect from people doing stuff that I’m stoked on. When we started doing that, I decided that we needed to come up with another name so that it wasn’t just focused on Static. I’m a mega nerd about conspiracy theories and alternate origins of civilization, and those were what all the books were about that I was reading at the time. So, I was trying to come up with a name that tied it all together. So the concept of Theories of Atlantis, which would take a whole other interview to explain its relevance, really worked. It’s kind of ambiguous—it doesn’t say skateboarding or anything like that, but it helps create a weird image in your head and it might spark someone’s imagination. So, that was the genesis of it.

“I WANTED TO DO SOMETHING DIFFERENT THAT WAS MORE THAN JUST A SKATE VIDEO— I WANTED TO DO SOMETHING THAT HAD TEXTURE TO IT.”

It started off as a blog essentially. I put up stuff that I was filming and I had our little web store. One of the guys that I was filming for Static III—this guy Soy Panday from Paris—he and his friend Vivien started forming their own skateboard company called Magenta. The company was out of Paris, but their boards were made in the United States. So, I told him that I would be stoked to carry a couple of their boards and put them in the web store as a way to kind of help promote it. That’s kind of how the distribution started. Then a couple of skate shops saw that we were carrying their boards and asked if they could get them from us. At the same time, I wanted to do a little brand based on the website called Theories, so we made our first T-shirt and tried to sell it at the Static III premiere. We did the premiere at the Village East theater and had a little merch table at the front. It was packed, but through it all, we didn’t sell one T-shirt! So the brand started at that point too—then through the web store, we sold a little collection of things from other people that we thought were cool.

How did you go about connecting with the other brands that are under the Theories umbrella like Hopps, Polar, and Traffic?

It happened organically in the sense that my friends started Magenta, and then I was doing an interview with Pontus Alv for the Theories of Atlantis website. He had just put out his video In Search Of The Miraculous—he’s an amazing filmmaker—so I wanted to do something on the site with him. During those conversations, he told me that he was starting his own brand. I told him about how we were working with Magenta, and that if he’d like me to carry Polar in the States, I’d be down to see if we could get something going. So, it stated serendipitously. Bobby Puleo and I used to work together at a restaurant, and it was something that I would always talk about with him. I would say, “Man, if we could get Traffic and Hopps,” and Bobby always wanted to start his own brand. But, we thought if we could have all of the East Coast underground brands under one roof, it could actually be something that would have some legs.

Each brand had struggled so hard on its own, but if we brought everything together, it would be really strong. So, it was something that we had already been talking about, then this other stuff started happening. Then we were welcoming brands as our friends were starting them—that’s what happened when Paul Shier started Isle. Most of them were people that I’ve done video parts with through the Static series—then they started doing their own thing, and it just made sense. That’s also what’s made it tough. I have a really strong personal connection with the guys behind each brand. We’ve tried to hit up other brands that I like, but it doesn’t fit as well because we don’t have the same connection. The last brands that we got involved were the two brands that inspired us to do the distribution originally: Traffic and Hopps. There’s been this surge of underground skater-owned brands over the past five years to the point where it’s almost a trend now. Hopps and Traffic preceded that by years. Hopps has been around for over ten years. Ricky Oyola and Jahmal Williams are East Coast godfathers—so I was stoked that we were able to get them on board.

From an outsiders perspective, the Theories brands seem wildly popular online. How does that translate into sales?

It’s tricky. The stuff sells a lot, we’re super stoked on how much support there is for it. But, I don’t think people realize how much competition there is out there. A couple of years ago, when most of these brands were just being noticed, there weren’t many brands that have that independent vibe and were in this sort of genre. As it was becoming popular, we saw the sales pick up a lot—and then over the past year or year-and-a-half, there’s been so many small brands popping up that it’s definitely diluted the industry a little bit. I don’t want to say that it’s hurt our sales, but the growth has leveled out a little bit. The tough thing for us is that we’re a distributor that doesn’t own its brands. If you look at Deluxe, NHS, and Crailtap, they own their brands; we’re just the middle man. That’s where it gets tricky, you have to sell so much stuff and you’re making such little profit. You have to sell a shitload just to keep your employees paid and to pay your warehouse, etc. That’s where something like the Theories brand helps, because it’s our own thing.

Given that it started as primarily a web store, what’s the current balance between online direct-to-consumer sales and sales to shops? Are they equal, or does one outweigh the other?

Our sales to shops far outweighs our online, but our online sales are definitely really significant for us. What’s really tricky about it is that because we’re a distributor, we always give our shops a leg up. When we get in product from Polar or even our own stuff, we wait to make sure that shops that ordered it prebook that season get it first and have a chance to get it up on their web stores first. It shoots us in the foot, but because we’re the distributor, we don’t want to compete with the shops that are supporting us. We’re trying to figure out the perfect equation that works best for everyone, but the web store definitely helps us because it helps balance out the fact that we don’t own these brands, but we are able to sell directly to the consumer.

“I THINK NOW, WHEN THERE’S SO MUCH MEDIA, THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE IS BEING REMEMBERED.”

Have you ever been approached by any of the big-box stores for any of the brands? Would you ever go that route?

I won’t name any, but we’ve probably been approached by all of them. We don’t own all the brands, so ultimately we leave it up to them, but as the distributor, we always recommend that we not do that. It’s never an argument. We all agree that that’s part of our appeal. It is more personal—like Pontus Alv with Polar—he’s filming the videos and editing them, he’s a pro skater for the brand, and he does most of the graphics. Magenta is the same thing—Soy Panday is drawing the graphics and skating in the video, and him and Vivien are helping edit the video. So, we all have such a connection to it, and skate shop owners connect to that. They need to see that we’re respecting that connection to skateboarding.

It’s tricky because there’s so much that goes into making a skateboard—there’s shipping fees, artist fees, and all these other fees, but the price remains the same. It’s so competitive with people making boards in China, so the smart thing would be to sell to those big-box stores as a business, but I think we would lose so much of the support that we have from people—especially from guys that were carrying these brands before they were cool and before people knew what they were. So, if I have my say, then we would stay in core skate shops exclusively.

Is Static IV / V the series finale or do you think you have another one in you?

I definitely have the desire. It’s mostly when I see something like the Isle video premier—when you see something really inspiring. Either somebody who does amazing work, or a skater that nobody knows about that’s really got something sick about their style. I definitely have the desire, but time wise it’s one thing—and then physically, I just don’t know if my body could take that kind of commitment anymore. I felt like I put so much time and energy into Static IV / V, that it would be impossible to do another video with that kind of commitment—so, I might as well let it end with those two. I’ve said that those are definitely the last, but I don’t like to say never.

I know in the past, you primarily dealt with hard copies, so I was curious about how you balance that when we’re in such a digital age with everyone watching things on their computer or phone. Is DVD still your preferred format for how people view your films? Do you have anything against digital streaming?

I’m not as opposed to online delivery as I might have been in the past. I feel like you have an opportunity with hard copies to extend the experience of the video with the packaging. With Static IV / V, we were able to tell the story through the packaging and get the theme or concept of the video across even more. I feel like we would have lost a lot by only delivering it online. To me, a big part of the fun was coming up with how we were going to package it, figuring out the booklet that came with it, and all of those details. That’s one thing, but also I think that if people have something physical, it has more value. When something is just digital, and just online, for some reason, it doesn’t have as strong of a perceived value. When it’s physical, it’s something that people will appreciate for longer. From where I’m sitting right now, if I turn around I can look on this little shelf and see the Underground Broadcasting video, Fully Flared, Underachievers, and Mind Field. I’ll walk by that once maybe every two months and think, “Oh shit, Mind Field—I haven’t watched that in a while.” If it’s just a file on your laptop, it’s forgotten after a week. I think now, when there’s so much media, the biggest challenge is being remembered.

“IF IT COMES FROM THE RIGHT PLACE, PEOPLE WILL CONNECT WITH IT.”

I feel like skateboarding is becoming more regional. We’ve been seeing these crews like Bronze, Dime, and even Palace to a certain extent become brands that have really resonated with people. I feel like Theories is sort of in that same lane, so I wanted to get your perspective on what you think that is?

I think you’re right about Palace in the beginning stages, and definitely Bronze and Dime—there’s a lot of other examples though, like the Far East Skate Network over in Japan. I feel like Magenta was sort of like that too—more in the earlier stages. I think it comes down to people don’t feel like they’re being sold something, it’s just a crew of dudes. Even like what John Wilson does, he doesn’t have a brand, all he does is make videos, but it’s a crew. People seem to really get inspired by a crew of friends having fun, and it’ll be a mixture of heavy skating, difficult stuff, and people having fun and interacting with pedestrians in a city. That seems like something that really resonates with people—not everyone, it’s almost like there’s two sides of skateboarding and two industries. There’s people who like that competitive/trying to push it to its limits skating, then there’s this whole market that seems to respond really well to that whole crew vibe. Dime makes tons of stuff, but it mostly just says Dime on it. People buy it to show their support, or to just show that they’re aware of it. A lot of it is probably that thing we had as kids. I don’t know if it was the same for you, but there was one other skater in my high school. When I saw him, he had a Girl shirt on and it was a way to recognize that I had something in common with him. I didn’t even have to talk to him, I just saw that and knew we were in the same secret society. Now that skateboarding is so huge, kids are like “I’m a skater, but so is everybody else—but I know about Dime.” Then he sees someone on the other side of the skatepark or spot and they have it on too and they instantly think, “Oh, that dude knows what’s up.”

What’s the biggest lesson that you’ve learned over the years through initially doing DIY skate videos and then expanding on that to create a website, distribution, and brand independently?

If you’re doing something for the sake of passion, or that you really care about and is fulfilling to you personally—and if you’re doing something for the right reasons, it clicks with people. I don’t know if people recognize that specific thing in what you’re doing, but if it comes from the right place, people will connect with it. If people are doing something because they love it and they have a unique voice or experience to offer, it’s amazing how broad the appeal can be, and how inspiring it can be to people. It’s crazy, I’ll go out to a place like Germany to a trade show and people will tell me that the first video that they saw was Cigar City, which was a video that I made when I was 16. The reach that things can have that you’re passionate about is incredible.