In the summer of 2015, I moved to New York during the 20th anniversary of the movie Kids. Because of my time in San Francisco, and my history with skateboarding in general, I was able to plug into that world and produce a series of editorial pieces with some of the members of the cast. Below you can read interviews with Leo Fitzpatrick and Carisa Barah that were originally published on the now-defunct Ride Channel website. And I’ve also included a link at the bottom to an article on Hamilton Harris’s five things you didn’t know about the movie—which is still live on The Hundreds site.

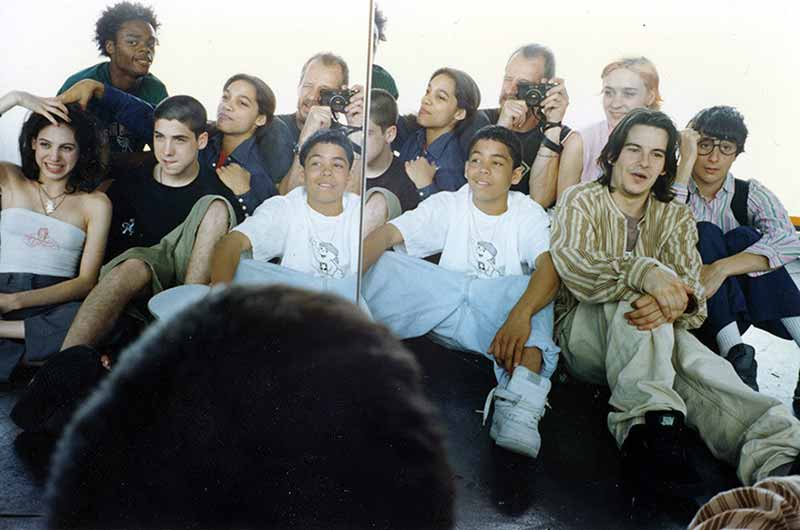

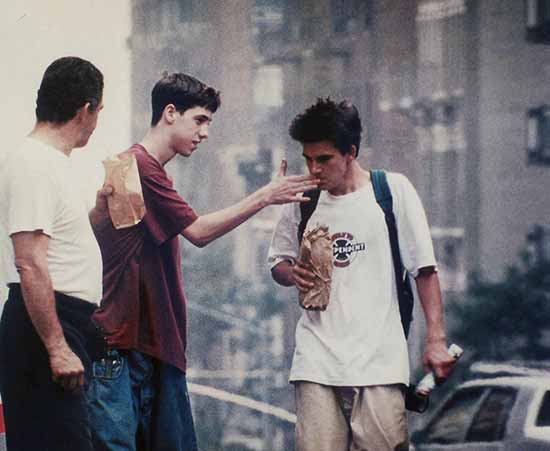

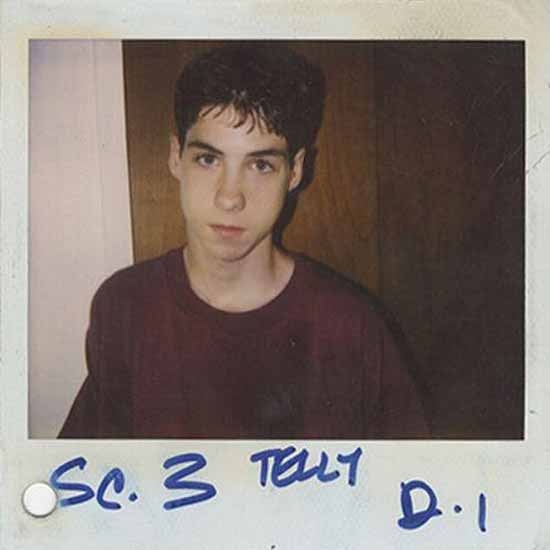

Today marks 20 years since the movie Kids opened in theaters. Larry Clark’s iconic 1995 film, which shed light on the darker side of growing up in an urban environment, has been heralded as one of the most important works to emerge from skateboard culture. For the uninitiated, it tells the story of Telly (Leo Fitzpatrick), an HIV-positive New York City skater on a mission to deflower virgins. He proudly shuns protection, and remains unaware of his status throughout the movie.

Along with Fitzpatrick, the film stars Chloë Sevigny, Rosario Dawson, Justin Pierce, and a sprawling cast of New York skaters, familiar names like the late Harold Hunter among them.

Given its cultural significance, Kids has been written about everywhere from Vice to the New York Times in recent months. We decided to celebrate its 20th anniversary by ringing up one of its leads, Fitzpatrick, who discussed its resonance both then and now.

What memory from making Kids stands out the most to you?

I don’t know, man. It’s weird for me because I’m not too nostalgic about it. For me, it’s just some shit that I did in high school. But I think just the whole thing in general. That summer in particular was really memorable. There were so many people in town from other places. New York had a really great energy that particular summer. The overall vibe on the set was that everyone was just hanging out. Nobody knew what making a movie was supposed to feel like. It more or less felt like a summer camp for misfits. Even if people weren’t working on the movie, they were still hanging out and coming by the set. It wasn’t too much different from our day-to-day lives, outside of the sex angle.

I guess what stood out the most was that we were being celebrated for what we were doing rather than being run out of spots and being told that we were punks. It was the first time that anyone ever championed us in a lot of our lives. That was really kind of a cool thing. I think overall, the whole experience of making the film is what stands out. Obviously, there’s certain moments like the pool scene was really great. You have to remember, I’m from New Jersey. I grew up skating with Tim O’Connor, Pancho Moler, and those guys. If you’re from New Jersey, people from New York very much let you know. Sometimes it was like the old Embarcadero days; if you weren’t a local, people would let you know by doing whatever they had to do. So I always felt like an outsider. In making that film, there was a little bit of acceptance that I didn’t have before. It was like, “All right, fuck—we’re gonna have to hang out with this guy for a month, so we might as well be cool with him.”

I guess what stood out the most was that we were being celebrated for what we were doing rather than being run out of spots and being told that we were punks. It was the first time that anyone ever championed us in a lot of our lives. That was really kind of a cool thing. I think overall, the whole experience of making the film is what stands out. Obviously, there’s certain moments like the pool scene was really great. You have to remember, I’m from New Jersey. I grew up skating with Tim O’Connor, Pancho Moler, and those guys. If you’re from New Jersey, people from New York very much let you know. Sometimes it was like the old Embarcadero days; if you weren’t a local, people would let you know by doing whatever they had to do. So I always felt like an outsider. In making that film, there was a little bit of acceptance that I didn’t have before. It was like, “All right, fuck—we’re gonna have to hang out with this guy for a month, so we might as well be cool with him.”

The one person who was always cool was Harold [Hunter]. Harold was kind of the mayor of the skate scene in New York City; he always played nice and got along. There were a lot of guys that weren’t cool. Me and Justin [Pierce] didn’t even get along. We weren’t friends in any way until after the film. You know, you’re 16, your ego’s getting a little bit out of control, you’re a little territorial. It’s not until you get a little older that you realize that acting like that is pretty ridiculous and we’re all trying to do the same thing.

What about the film still resonates with people 20 years later? Why do you think people are so fanatical about it?

I have no fucking idea, man. I haven’t seen it in 20 years, but I would imagine that it’s just the idea that—the film is supposed to be a cautionary tale. It’s not supposed to be a feel-good, get-pumped movie. But I think it’s just that freedom that you have as a teenager. The idea of running around with your crew and kind of creating your own fun even if you don’t have much money, and sort of not knowing where the day is going to take you and not having an agenda or responsibilities. More things happen to you in your teenage years than will happen to you in the rest of your life. There’s more firsts: the first time you drink, the first time you smoke weed, the first time you have sex—those are all firsts. Once those are gone, they’re gone. I just think the idea of being a teenager and discovering things is kind of what people can maybe relate to, and that that movie is part of a discovery. But if you watch other movies like Over the Edge, which is a little younger, all teenage movies are pretty great. They just symbolize a time in your life. At the time, it doesn’t seem simpler because mentally you’re going through so much shit, but it is a lot simpler—you don’t realize that until you’re older and you’re like, “Fuck, I wish I was a teenager again. That was sick!”

That was the first role for you, Chloë, and Rosario. All of you guys have gone on to continue acting. What do you think it was about that film that made you guys catch the acting bug?

I can’t speak for Rosario or Chloë. I think that they adjusted to it a lot better than I did. Like I always say, I never intended to be an actor—I was just a failed skateboarder. In my dreams as a kid, I would have been a pro skateboarder, but I just wasn’t that good. Basically, in life you start running out of options as to what it is that you’re going to be doing with the rest of it. I didn’t act for a long time after the film. A lot of people were kind of confused by that. I said, “You know, Hollywood is a weird fucking place. I don’t know if I want to be a part of it.” It wasn’t until I was older that I could do it. I was just more comfortable in my skin and I didn’t care what Hollywood thought of me. So Kids was an opportunity that I eventually built on. I’m still not 100 percent comfortable with acting. I have a day job—I work at a gallery. It’s not like real day job, but I  work in here. It’s weird to get thrown into something that you never thought about before and it’s in a public forum. I like being anonymous. I’m kind of like one of those weirdo loner skaters. I like to be able to walk around or skate around and nobody knowing who I am. That kind of disappears a little bit when you’re an actor. For me, acting is cool, but I very much look at it as a job. I show up to work, do my job, and then I go home. I don’t really care about this fame angle. Money would be nice, but that eluded me so far. There’s not that many opportunities out there for a lot of us. If you get one, you should kind of chase it. I think Chloë and Rosario have it a little easier than me, but I was such an odd kid anyway. I was such an odd casting decision that I don’t think Hollywood knows what the fuck to do with me. For me, I take it all with a grain of salt and I’m just thankful for what I do, but I’m not really trying to be a famous actor. I’ve got bigger ambitions than that.

work in here. It’s weird to get thrown into something that you never thought about before and it’s in a public forum. I like being anonymous. I’m kind of like one of those weirdo loner skaters. I like to be able to walk around or skate around and nobody knowing who I am. That kind of disappears a little bit when you’re an actor. For me, acting is cool, but I very much look at it as a job. I show up to work, do my job, and then I go home. I don’t really care about this fame angle. Money would be nice, but that eluded me so far. There’s not that many opportunities out there for a lot of us. If you get one, you should kind of chase it. I think Chloë and Rosario have it a little easier than me, but I was such an odd kid anyway. I was such an odd casting decision that I don’t think Hollywood knows what the fuck to do with me. For me, I take it all with a grain of salt and I’m just thankful for what I do, but I’m not really trying to be a famous actor. I’ve got bigger ambitions than that.

I think that you’ve remained the closest with Larry Clark after the film. You did Bully with him, and more recently you do a series of shows with his photography from Kids. Tell us a little bit about your relationship with him, how you’ve maintained it, and what the dynamics of that are.

Me and Larry very much have a father-and-son relationship. He got me into all of this shit. He introduced me to acting, art, and a lot of stuff. So with the $100 print sale, it’s nice that I can sort of pay him back a little bit. Larry’s just like a straight shooter. He’s not like an adult; he doesn’t judge kids for being a little crazy or trying to discover themselves. He’s just kind of a genuine person and he’s an artist. He appreciates people that are a little off and do things their own way, because that’s how he’s always done it. We see each other at least once a week. He sort of replaced my father at some point. It’s weird—I don’t think people understand how much he really loves and respects everyone that he works with and just teenagers in general. He gives them more respect than any other adult that they’ve probably encountered. It’s funny—now that I’m older, unless I play a parent in one of his films, we’ll probably never work together again.

Can you give a little reflection on Justin Pierce, since he was your co-star in the film and is no longer with us?

Can you give a little reflection on Justin Pierce, since he was your co-star in the film and is no longer with us?

I was friends with Justin, but I won’t claim to be his best friend. I didn’t know him the longest; there’s a lot of people that would have more information. But Justin was a super-magnetic guy. He was the cool guy on the set. He was the guy that you wanted to be. The girls had crushes on him and the guys wanted to be him. It’s weird when you come to the realization that sometimes people can give off this vibe, but truthfully they’re not as comfortable in their own skin as you would think. Justin was Justin. He didn’t really try to please anybody or play by the rules—he did what he wanted to do.

I think his suicide was simply a drunken mistake. It was nothing more than that. I think that if he’d slept it off, he would have woke up the next day. I think that we know a lot of people that have probably thought along similar lines. It was just a dumb, drunk mistake. You know, it’s tricky to navigate life and be that young and confused. It’s just bad for everybody. It’s just a bad thing that happened. Coming from skateboarding, we know a lot of people that don’t know what to do with  themselves after skateboarding. They fill that void with drugs, alcohol, and other things because they can’t jump down stairs any longer. The idea of beating the shit out of yourself every day on a skateboard to roll away from a trick once, and that’s the only satisfaction that you get, there’s something masochistic there—there’s something wrong with you. That’s your form of therapy or dealing with shit: “I’ll just go out and beat the shit out of myself.” The less you skateboard, the harder it becomes to fill that void, and you think, “Drinking is pretty rad, doing drugs is pretty rad, that’s a good way to beat the shit out of myself.” Obviously skaters have a harder time transitioning into life than I think the average person does.

themselves after skateboarding. They fill that void with drugs, alcohol, and other things because they can’t jump down stairs any longer. The idea of beating the shit out of yourself every day on a skateboard to roll away from a trick once, and that’s the only satisfaction that you get, there’s something masochistic there—there’s something wrong with you. That’s your form of therapy or dealing with shit: “I’ll just go out and beat the shit out of myself.” The less you skateboard, the harder it becomes to fill that void, and you think, “Drinking is pretty rad, doing drugs is pretty rad, that’s a good way to beat the shit out of myself.” Obviously skaters have a harder time transitioning into life than I think the average person does.

What projects are you working on right now in the art world, or do you have any acting projects coming up that we can look out for?

My main gig right now is in the art world, I have a new art gallery popping up starting in mid September called Viewing Room, which will be in this gallery called Marlborough Chelsea that’s in Chelsea. That’s my own programming—just regular old art world shit. Acting-wise, the only thing I have coming that’s not just some indie movie that I shot 20 years ago that might be coming out is I just did a little thing in the new Pee-wee Herman movie. I can’t talk about it too much because it’s a big-deal movie and there’s confidentiality and all of that, but Pee-wee is rad—he’s a good dude. That’s the acting that I enjoy doing now—stuff that you wouldn’t imagine that I would be doing.

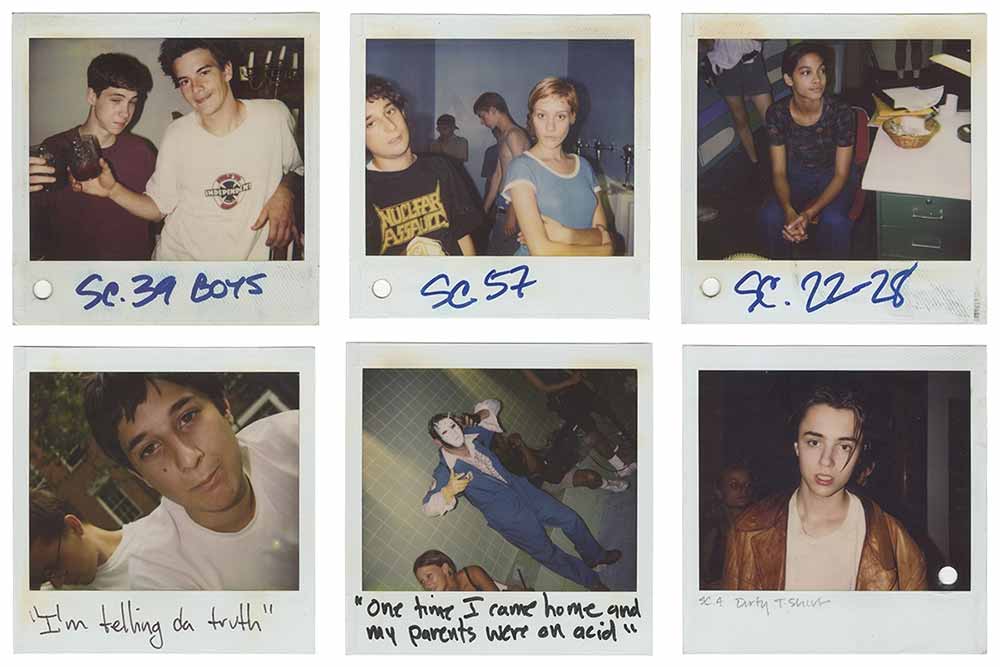

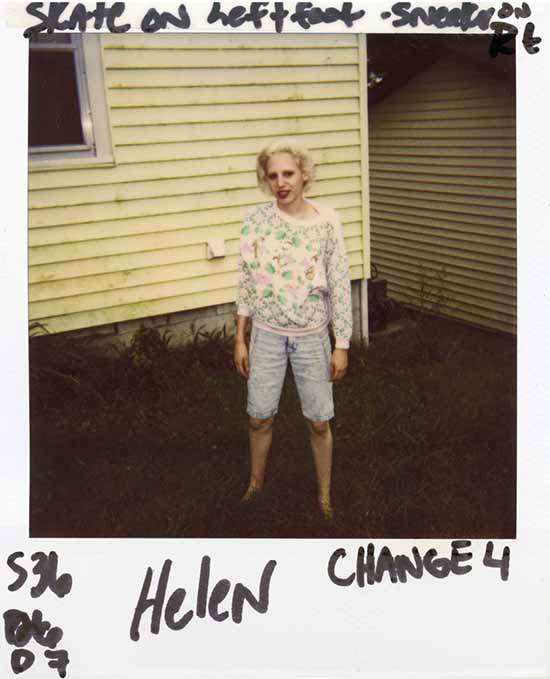

If you’ve seen the movie Kids, from 1995, you should remember Carisa Barah, who played Joy. Credited as Carisa Glucksman, she was one of the girls roaming the streets with Justin Pierce, Harold Hunter, and Leo Fitzpatrick. She shared the infamous girl-on-girl kiss scene in the pool, and she was featured prominently in the film’s climactic party scene.

There’s been a lot written about Kids of late, especially in light of the fact that a new documentary about the movie—produced by some of the people in it, skater Hamilton Harris among them—recently met its fundraising goal on Kickstarter. But given that the film has thus far largely been recalled from a male perspective, I thought it would be interesting to talk to one of the women who appeared in it and get a female’s take on what it was like to make Kids and live through that era in New York. So I contacted Carisa and she agreed to a phone interview on the topic. We also discussed her roles in Harmony Korine’s Gummo and Steve Berra’s 7-Teen Sips, her move from New York to Los Angeles, her friendships with legendary skaters like Keenan Milton and Guy Mariano, and her current battle with an autoimmune disorder that caused her to make some serious life changes for the better.

You’re from Brooklyn. Were you hanging out downtown around skaters when they were casting Kids? How did you end up getting into the film?

Chloë [Sevigny] was one of my best friends at the time. She had been away for part of the spring. I wasn’t really in the skate scene; I was much more heavily into the rave scene. They were casting people in clubs and out in Washington Square Park. I had been approached several times to come in and audition. I was actually kind of “whatever” about it. Then Chloë came back to New York, and I hadn’t seen her for a while. We had written postcards and talked on the phone, but I hadn’t seen her. I had a crush on this breakdancer, and I really wanted to tell her about this crush. She wouldn’t listen to me until I went and auditioned for the film. We literally stood outside this store on Houston and she said, “Go now, and then I will listen.” So I went and auditioned for the film so I could go and tell her the story about the boy. At that time, I got a smaller part, and Chloë originally had my part. Then things changed with the casting—the lead actress didn’t work out, so she ended up getting the lead and I ended up getting her part, which ended up being Joy.

You would have been about 16 or 17 when they were filming that movie. You mentioned that you were more into the rave scene than the skate scene. Do you think the movie was an accurate depiction of what was going on around you and what you were seeing in the city?

Yeah, to a point. I was kind of a late bloomer—everyone was having sex and doing all of these things, but I was very naive. There was an innocence and a lawlessness—that’s how we were all behaving. I’m really grateful that I grew up exactly when I did, because it’s not that way anymore. There’s no more innocence. There’s no more disconnection. There’s no more grit. Everything has to be so polished. It was really nice.

Outside of Chloë, did you know any of the other cast members prior to shooting the film?

I knew Harold [Hunter]; we definitely hung out quite a bit. I knew Justin [Pierce], I knew a couple of the skaters—but not really. I knew whoever was into the club scene. I always thought skateboarders were so brash and obnoxious, so I didn’t really feel very comfortable around them. I definitely hung out with them. I hung out down at the Cube [Ed. note: Astor Place]—but that didn’t really feel like I was hanging out with skateboarders. It was always just after the club, or roaming around not knowing what to do. It was more just running into people, and not a thought-out plan.

Being that you were so young, was there anything in the film that you were uncomfortable with? There was the pool scene where you had make out with Michele Lockwood. Were you comfortable with shooting all of that stuff, or was it kind of awkward?

It was the first time that I had ever kissed a girl—that was a little bit awkward. But I knew exactly what I was getting into—my parents had to sign the contract in order for me to be able to do the film. I was nervous about that scene, but it was fine—Michele is a good kisser. It wasn’t very nerve-wracking. The idea of being on film was nerve-racking in and of itself.

What about the party scenes? I know some of the cast members were smoking weed on film. Were you worried about that and having that stuff documented?

I didn’t really worry about it. My focus was actually that Ravestock at Woodstock was having their 25th anniversary happen the following day—going to that was more important than whatever was going on that night. It was a night shoot, and there was lots of down time. It’s not like you’re partying all night and you get taken by the adrenaline of the evening. There was just a lot of hanging out on the street killing time between shots. I didn’t really have any apprehension. There were actually way too many skaters for me, and way too much machismo for me—I just wanted to go upstate and party for the weekend.

What was life like after the film? How did your friends and family react to it, and did it open up any opportunities as far as acting, modeling, or things like that?

What was life like after the film? How did your friends and family react to it, and did it open up any opportunities as far as acting, modeling, or things like that?

My mom saw it, and she was worried that that was what was going to happen to my brother. It took my dad several years to watch it. He really liked it; he just didn’t understand why Larry Clark didn’t shoot it in black and white. He just thought that it was such a documentary format, that that could have added another level. But I’m really glad that it’s in color. But yeah, even now—I don’t tell people that I was in the film, but it comes up. It’s something that still really resonates with people. People definitely take notice, and they did then. I think it lubricated certain conversations for people to have, where I then got an opportunity to do certain things because of the film. I already had the talent, but the doors opened up for a lot of things—I designed my own line for Fresh Jive. I assumed that they liked the fact that I was in Kids and had been in Gummo. There was that framework to bounce things off of when he was trying to sell the line. I never really tried to act. I really just was lucky. Chloë just pushed me in the direction of auditioning.

You just mentioned Gummo, which leads right into my next question. You worked with Harmony Korine again on that film in 1997. How did that happen? Was that just through being friends with Harmony and Chloë?

Again, it was because I ran into Chloë. She said that Harmony was trying to reach me, and didn’t know how. This was in ’96—we shot it in ’96. I remember Tupac dying while we were shooting it. We shot it in the late summer and early fall. Anyway, Harmony was looking to talk to me and see if I fit what he wanted. So I came over and auditioned for Harmony and Chloë, and it felt natural, so that’s how I ended up in Gummo.

Eventually you ended up in Los Angeles. What took you to the West Coast, and what was your career path when you went there?

In New York I felt like I was doing things for everyone else and not me. Originally, I actually moved to Utah and lived in Salt Lake for three months. At first I wasn’t going to move to L.A. My best friend lived here, but I wasn’t going to move to another city because she happened to live here. My brother came to Salt Lake to go snowboarding and visit me, and we took a trip out to Los Angeles. My brother is a skate photographer, so we went out there for that—I actually got immersed in skateboarding then. On that trip, I had such an awesome time—we were hanging out with all of the Girl and Chocolate guys and the Menace guys. I just had the best time, and I realized that there was obviously more opportunity in Los Angeles. Back then, I wanted to design clothing—so there was more opportunity here than in Salt Lake. So I just decided to move. When you’re 19, it really is just that simple. I learned how to drive in Utah. That was my mission—to learn how to drive before I got here. I moved in the spring of ’97.

You were also in Steve Berra’s film 7-Teen Sips, which never got a wide theatrical release. You actually can’t get that film in physical or digital form anywhere. Can you tell us how you got involved with that project and share any general information about that film?

I don’t remember much of the premise of the movie. I used to have a box where I kept all three scripts, and I don’t know where it is. It bothers me, because I really wish I had them. But from what I remember, 7-Teen Sips had a similar premise to Bully—it was very dark. I played a goth girl. I don’t remember the character’s name. Again, it was happenstance. I was at a Chocolate premier, and I guess at that time I was trying to act. I wasn’t really trying, but I was trying—and I was thinking about moving to Paris. I said to people really casually, if I get a film, I’ll stay in L.A. I was going to buy my ticket the next day, and I ran into Steve, and he said, “I really want you to be in my movie.” So I decided not to go to Paris and stay and do a movie. I spent a few weeks in Nebraska—I think we were in Lincoln. It was hot. It was, like, 117 degrees. Bam Margera was in it. It was nice to be on location, and Steve’s a really great guy. It went to Slamdance. I think at that time, Slamdance was really small. I think now it’s a much bigger deal. I think it was Steve’s first foray into directing. He had been writing for a while, but I don’t think that he had directed before. So, yeah, it was a great experience, but I don’t really remember all that much.

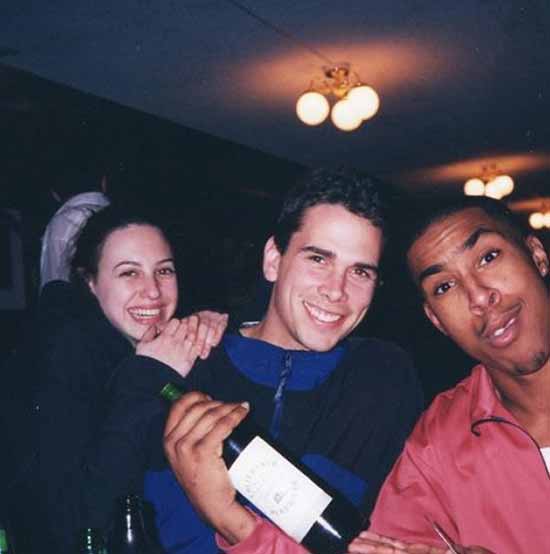

Yeah, it was a long time ago. I just wanted to ask you about it because it’s sort of a mystery in the skateboard world. I actually used to work for Steve, and he doesn’t really like to talk about it because something happened with the distribution that made him unhappy with the project. But moving on, I saw a photo on your Instagram of you with Keenan Milton that looked to be around the time that he passed away. Were you close with him and Guy Mariano and that crew, and can you give any stories from that time period?

Oh, that’s the one of me, Hilary, and Keenan in the hammock. Hilary passed away soon after Keenan, so that’s a really heavy picture. Keenan was just like an angel. He really was. I can still remember his laugh. I can hear his laugh so easily. Him, Guy, Gino [Iannucci], and all of those people are partly responsible for me moving to Los Angeles, because I just had the best time with them when I visited. I didn’t know that there was going to be this longevity to our friendship of almost 20 years now, but they are just awesome individuals. I think Keenan nicknamed me—it was either Keenan or Guy. I think I was one of the only girls that hung out with all of those guys consistently. I was so small and petite that they would always call me Little Dude, because I was such a tomboy. It was such a tragedy when Keenan died. It’s still painful. It’s such a loss, because he was so young—and he had so much ahead of him.

Oh, that’s the one of me, Hilary, and Keenan in the hammock. Hilary passed away soon after Keenan, so that’s a really heavy picture. Keenan was just like an angel. He really was. I can still remember his laugh. I can hear his laugh so easily. Him, Guy, Gino [Iannucci], and all of those people are partly responsible for me moving to Los Angeles, because I just had the best time with them when I visited. I didn’t know that there was going to be this longevity to our friendship of almost 20 years now, but they are just awesome individuals. I think Keenan nicknamed me—it was either Keenan or Guy. I think I was one of the only girls that hung out with all of those guys consistently. I was so small and petite that they would always call me Little Dude, because I was such a tomboy. It was such a tragedy when Keenan died. It’s still painful. It’s such a loss, because he was so young—and he had so much ahead of him.

Skateboarding still mourns losing Keenan for sure. Moving on to more current times, I checked out your website. Now you’re a holistic health coach and that happened because you developed an autoimmune disorder. Can you give a brief history on how you got to where you are right now?

Yeah, my life turned on its heels. I was fine one day and not fine the next. I was in severe pain, and I was running to the bathroom close to 25 times a day. I thought I was dying. I was walking into the emergency room, and it was one of the most terrifying experiences of my life. I never felt so far away from my family. When I got sick, I didn’t even know what I had was chronic. I don’t even like using the word chronic, because that means that it will never get better—and I don’t believe that. I ended up having a digestive issue, and went to a gastrologist—and he told me that I didn’t need to worry about what I ate! He said that if you eat something and it doesn’t agree with you, don’t eat it again—it was so crazy! I was in so much pain, and these doctors were like, “Don’t worry about the food, here’s a pill.” I’m not against Western medicine, but that level of disconnection to how we treat our bodies made no sense. So I started doing my own research. I feel like it’s incredibly important to take personal responsibility for how our bodies behave. That means putting things into play such as diet, exercise, and medication. It takes a variety of lifestyle changes, but especially diet. We’re putting foreign matter into our bodies every single day. We can detox and handle a certain amount of things that are foreign to our system, but we have far surpassed the level of what our bodies can actually handle. So, the dial is now at 11, because all we do, as a general rule, is eat crap. We’re part of the animal kingdom, and the animal kingdom eats real food—they’re not going and getting a slurpee at 7-11. We have to give ourselves real food if we expect our bodies to behave in the way that we’d like them to. So that’s how I got into that—I’m sure you can hear the passion in my voice, because I’m really passionate about this. My personal battle brought about a huge change. It wasn’t just in my digestive system. The side effect of me cleaning up my plate is that I cleaned up my brain. I cleaned up my anxiety, I cleaned up my depression—things that had been staying with me for 20 years went away. Now, I’m a certified yoga teacher. That was the next thing on my list—getting my physical and mental state of being healthy. Now, I want to bring that to others as well. It’s something that’s so horrible, and I wouldn’t wish it on anyone in the world. But it ended up being the best thing ever.

Wow, that’s a pretty amazing story. So now you’re in good physical health after that transformation?

Wow, that’s a pretty amazing story. So now you’re in good physical health after that transformation?

I feel really good—the best that I’ve ever been, but I still struggle. What having an autoimmune disease, and there’s so many, means is that our bodies are attacking ourselves. So I’m in a constant battle to train my body, and I’ve done a really successful job so far. A lot of people in my position are on some insane medication—it’s like chemo for your gut. I’m on the lowest dose of medication, and I do a lot to try to keep myself as stable as possible. I hope one day to not be on medication, but if I am, I hope that I only have to be on the one that I’m on. It’s the best out of so many that are really horrific.

Very interesting. So the final question is that the Kids documentary actually hit its goal on Kickstarter. Are you going to be participating in the film? Have you been in touch with Hamilton Harris about it? What can you share with us?

I will be participating, as far as I’m aware. Thanks for reminding me that I need to respond to Hamilton’s email about it, because I forgot. He hit me up a couple of weeks ago, and things have kind of shifted a lot. But yeah, I’m really excited, and I’m glad that they made the goal that they needed to make and that there were so many people that came out in support of what they’re trying to do. I’m going to support it in any way possible. I believe that once they get funding, that they’ll start doing more interviews and getting things together.

After our in-depth conversation with Hamilton Harris about the Kids documentary that he’s working on—20 years after starring in it himself—we decided to follow-up with him and get an insider’s perspective on what it was like working on the original film. We asked him to tell us five things that the general public does not know about the movie Kids. He obliged us with some answers that are quite surprising, given how celebrated the movie is in popular culture. While this film launched the careers of A-list celebrities like Chloë Sevigny and Rosario Dawson, and has been written about in various mainstream publications including Vice and The New York Times, there is much about the film that is still unknown.